Julia Lambright

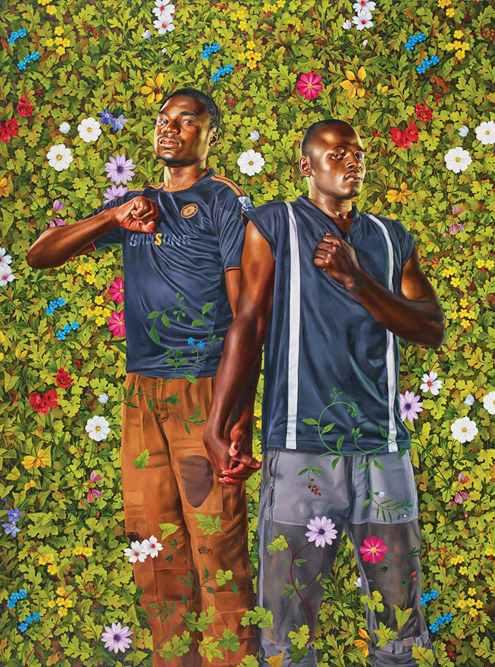

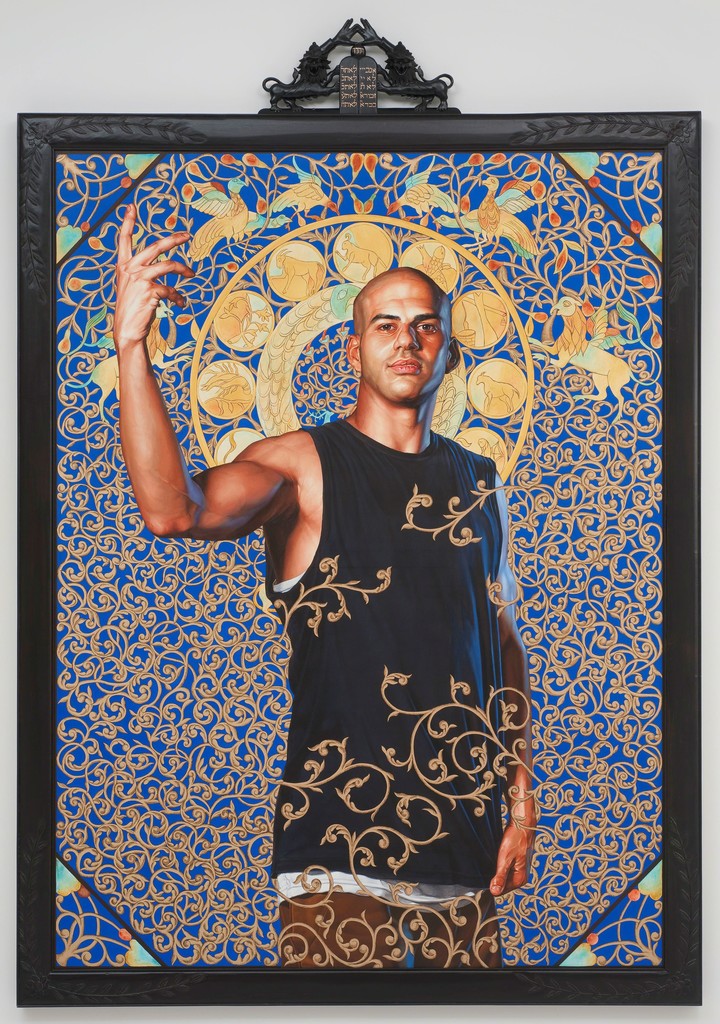

The artist that sticks out as the most relevant to my work so far is Kehinde Wiley. He is known for his beautiful paintings composed of larger than life photorealistic figures accompanied by bright, eccentric backgrounds. His work is at once captivating and thought provoking; blurring the boundaries between traditional and contemporary forms of representation. By taking black men (and more recently women as well) from urban areas and placing them in poses to mimic those of famous early traditional paintings, he creates a fusion of period styles; merging the old with the new. These heroic portraits in turn address the image and status of young African-American men in contemporary culture.

At the beginning of his career, Wiley began to gain recognition for these paintings after basing his works off of photos of young male figures he found primarily around Harlem’s 125th street as well as his home in South Central Los Angeles. As time passed however, he expanded his range to urban areas of cities around the world. Using oil paint on various surfaces including canvas, wood panel, and linen, he renders these figures photorealistically in the poses of paintings from Renaissance masters such as Tiziano Vecellio and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. By doing this, he is essentially placing these young black men within that field of power originally bestowed upon noblemen and royalty.

My immediate draw to Kehinde Wiley came from the pure beauty of his paintings. I have always been fascinated with photorealism, and to see it so beautifully mixed with multiple modes of expression as well as the incorporation of a deeper statement and meaning was amazing. One quote I found from Wiley when researching him further was particularly interesting to me. Of his early days in art school, he said, “I just liked being able to make stuff look like other stuff. It made me feel important. ... So much of what I do now is a type of self-portraiture. As an undergrad ... I really honed in on the technical aspects of painting and being a masterful painter. And then at Yale it became much more about arguments surrounding identity, gender and sexuality, painting as a political act, questions of post-modernity, etc.” This really resonated with me because I have struggled recently with my overwhelming draw to perfect the technical aspects of my painting, and have struggled to merge that with the statement of my artwork. In other words, I have not yet discovered what I want to say with my work. There have been multiple occasions in which I have even questioned if I wanted to pursue art, as I felt as though nothing I had to say was important enough. But I think what I have realized is that you can’t force meaning on an art piece. Perhaps it is better to spend time perfecting the technical aspects of your work and let the inspiration for your statement come naturally. Because once you force a message into your work that you don’t truly advocate for, it loses any meaning it could have had.

-